“MATAR LOS TEXIANS”

By Bob Jamison

TRANSLATION: “Kill the Texans!”

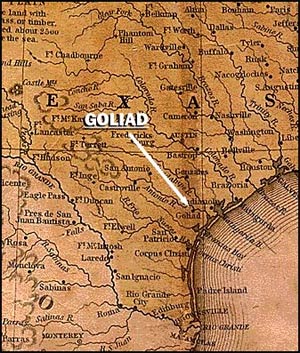

That was the dreadful order given on March 27, l836 in Goliad. Also the captives of loyal Texans in the various battles of the Texas Revolution that were executed numbered greatly during the campaigns prior to the Battle of Jan Jacinto in April.

In fact, significant fighting began in June l832 at Velasco (now greater Freeport called Surfside), because the Mexican fort on the Brazos fired on a Texas schooner loaded with guns headed to Anahuac. But the first really official battle of the Texas Revolution began later in Gonzales in October l835. By the time March 2, l836 rolled around, the Convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos was held and passed the Texas Declaration of Independence and the fighting really started then.

Hope for reinforcements to the Alamo from La Bahia at Goliad, Texas was dashed as captured Texas troops were divided into groups and marched down the road near the old Mission La Bahia. Their fate was uncertain as they had fought bravely in the Battle of Coleto Creek and were eventually captured when superior Mexican forces surrounded their square position of defense. Three officers of the Texas revolutionaries sent a message to the Mexican officials that they would surrender only as honorable captured soldiers and should be treated as such. It was signed by James W. Fannin and two other officers.

General Jose de Urrea was in command of the Mexican forces at the time and assured Fannin that he knew of no occasion when a prisoner of war was harmed by them. Urrea did have the reputation not being blood-thirsty and assured Fannin he would appeal directly to General/President Santa Anna for clemency; which he did. Then before an answer came Urrea was sent to another command.

Major Juan Jose Holsinger, one of the Mexican commissioners calmed the prisoners that they would return home when word came from Santa Anna. It came alright. The orders were to comply with a decree of the Mexican Congress dated December 30, l835 which directed that all foreigners taken in arms against the government of Mexico should be treated as pirates and shot. That decree was requested and authored by President Santa Anna himself.

When the firing stopped, while still in hearing distance of the Mission in Goliad, three hundred and forty two brave Texans were dead including Fannin. Twenty one were spared as they were important to the Mexican cause such as doctors to treat wounded Mexican soldiers, blacksmiths, interpreters and mechanics. However, twenty one did manage to escape.

The Mexicans piled up the dead and set fire to the bodies. On June 3, l836 General Thomas J. Rusk led troops through Goliad while in pursuit of General Vincente Filisola’s retreating army. When he saw the remains of the massacre he ordered his troops to bury what was left from the fire, coyotes and vultures. Only until l930 that some Boy Scouts found burned human bones that the actual site was identified by anthropologist such as J. E. Pearce from the University of Texas. It was later verified by historians Clarence R. Wharton and Harbert Davenport.

After the executions that rang in the ears of the Texas Revolutionist, shouts were later heard, “Remember the Alamo---Remember Goliad”. That became known as the battle cry as General Sam Houston’s tactics, though thought to be fearful retreat by many, brought the Mexican army led by Santa Anna to San Jacinto. In twenty seven minutes the battle was over and Texas was free.