DID OUR COUNTRY GET A KICK OUT OF WHISKEY?

By Bob Jamison

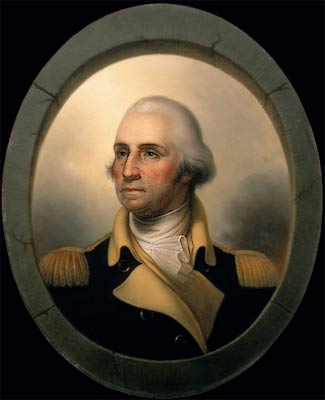

Whoa! Who would have thought of it? But, take a look. It might be more logical than it seems. Back in the years of the “Colonies”, if you didn’t own a farm you might not eat. George Augustine was no exception though he reached high in the annals of our history even before the American Revolution.

In those days, if you ran for office (even the Congress of the United States) you had better have a financial backup to sustain your livelihood (not so in this day and time). This even included soldiers of our brave forefathers that used mostly their own guns and clothes to defeat the greatest army of the world, the British. Yet they might have returned home to plant their crops or harvest them even while serving.

George enjoyed politics and truly had the best of the country in mind as history proves. But he also had great responsibilities at home. Agriculture was iffy at best. Prices of crops were truly based upon supply and demand. However, the demand was essentially on the eastern seaboard, many miles from Virginia. Grain was always in demand but transportation was lacking efficiency and often the grain arrived molded or spoiled.

As luck would have it, one of George’s employees was a Scot that had a knack and more importantly, a detailed knowledge of making spirits out of grain. He convinced George that converting corn into whiskey would not only preserve the precious grain from spoilage but protection from the drastic fluctuation in commodity prices. (Sounds like today). So, George agreed with his trusted friend, John Anderson, the manager of his new plantation in Virginia when he persuaded him to let him set up a still. This would ensure safe delivery to the east coast and a heck of a lot easier to sell.

Anderson learned the distillery methods in his homeland in Scotland. George had a barrel making plant and a grain farm with two hundred slaves. He had plenty of fresh spring water and ample products. All it needs was a little know-who and heat. Actual scotch whisky is spelled without the ‘e’.

The first step in making alcohol was called malting. Barley was saturated with water which caused it to sprout. Then it is dried on a sheet of metal to stop germination. When dry, the malt, rye and corn were ground at George’s gristmill. It was then poured into vats and stirred with water to cause the starch to change to sugar.

Anderson’s recipe was 60% rye, 35% corn and 5% malted barley. The distiller added yeast and let it set for several days. It was then transferred to stills and heat was added to l60 degrees. As the evaporation went through copper coils it returned as clear alcohol. Later, wooden kegs changed the color and taste or additional distillation caused the whiskey to have a more palatable acceptance.

George made many investments in lands toward the west. However, much land was given free to bring farm land westward so there was little but a buyer’s market. Something had to change. Whiskey seemed to be ready for a very acceptable market. The first still led to an impressive profit and others were to follow until five stills were producing a combined six hundred gallons per run. In the year 1799 a whopping 11,000 gallons were produced.

All this time while George was in the Congress, the Whiskey Rebellion happened like the Stamp Act, Boston Sea Party, etc. He led against the rebellion because it would bring in much needed revenue. Yet he himself always paid the proposed tax on his production of the whiskey market.

George sustained his proper place in history as the greatest man on earth as he was called after the war by the King of England. Of course, you know him as George (Augustine; his father’s name) Washington, the father of our country.